The spring equinox fell on Thursday 20th March this year.

It is the moment when the sun crosses the celestial equator and moves north, so that day and night are equal in length all over the world. This balancing act lends the equinox its name, which comes from the Latin aequus - ‘equal’ - and nox - ‘night’.

That evening, I went to Daunts bookshop in Marylebone, London to celebrate the launch of Merlin Hanbury-Tenison’s debut memoir, Our Oaken Bones. It was a good book to go out into the world on equinox night. It tells the story of one of the last fragments of temperate rainforest left in England which lies on a 300-acre Cornish hill farm where Merlin grew up and where he now lives with his wife, Lizzie, and their young family.

This old forest helped Merlin recover from the trauma of war which broke him and helped heal Lizzie’s pain of recurrent miscarriage which nearly broke her. But while the book - and the Thousand Year Trust formed alongside it - is a plea for us to understand, value and protect these ancient and important rainforests that few people know still exist, it is also an old story of how light and dark sit together in the way the spring equinox makes us remember. Maybe this is why this point in the year has been marked in one form or another by so many people for so long.

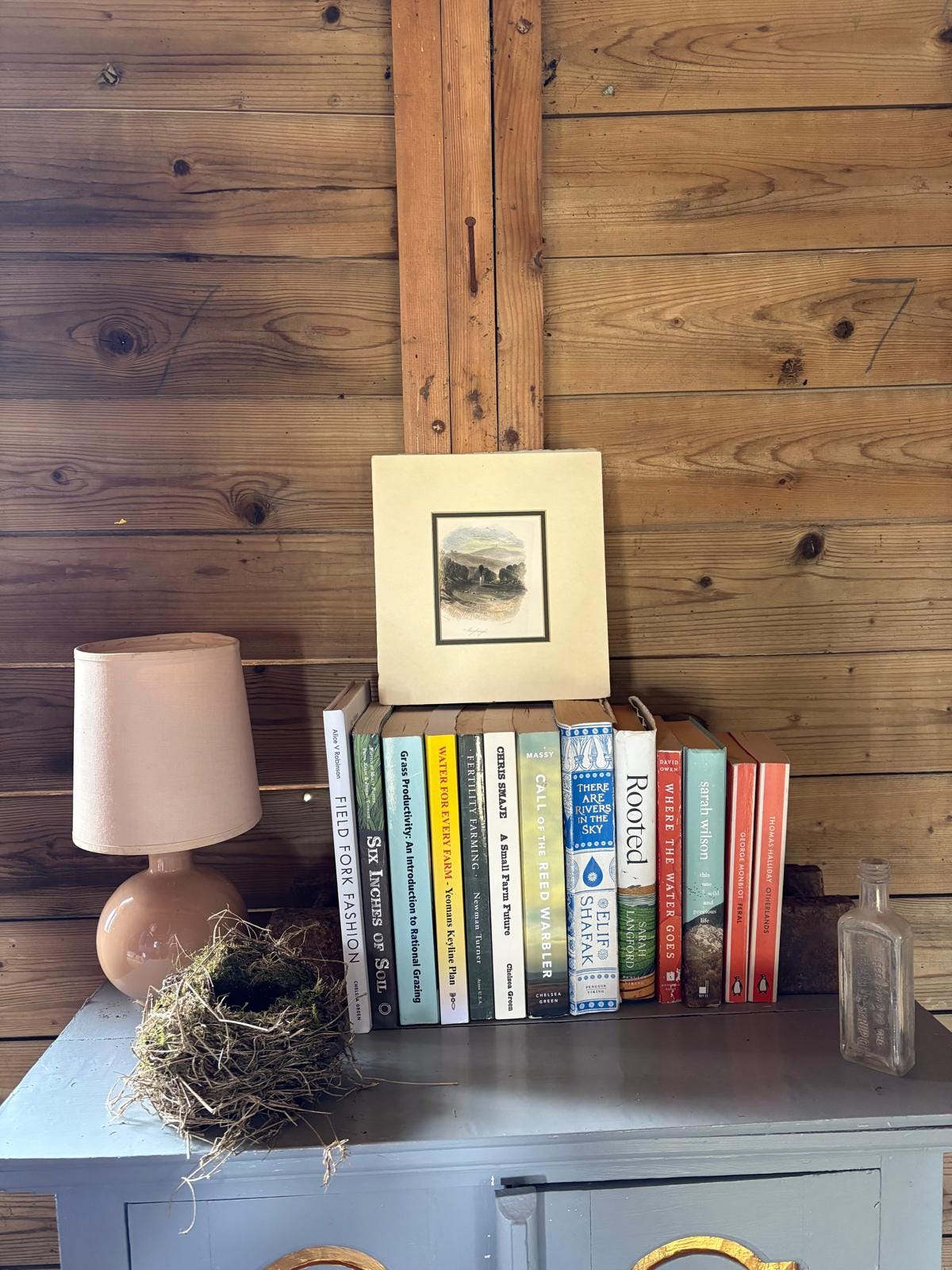

In my book, Rooted, I wrote about the old pre-Christian pagan festival Ostara (or Eostre) which used the equinox to celebrate fertility and new life, using symbols we still use for Easter even if we do not remember where they first came from, like hares and eggs.

I wrote this:

The day I first hear the bullfinch is the spring equinox, falling two-thirds of the way through March. Now night and day are equal length, but soon the light will lengthen, banishing the dark. The need to mark this change has always been felt strongly by country people, right back to a pagan festival named after the Anglo- Saxon goddess Eostre, who was said to have represented fertility, birth and rebirth. Even now its Christian replacement, Easter, is still tied to it, always falling on the first Sunday after the full moon following the spring equinox.

On our way home the children and I see a hare running along a neighbouring farmer’s newly greened- up crop. Here in Suffolk they are neither common nor rare, although this is not the case in other parts of the country. Their numbers have fallen by 80 per cent in the last hundred years. We have seen hares here before, but this time we are far closer to one than we ever have been. It stops when it senses us, freezing still. Time is suspended. I am struck by just how long its ears are and by the power of its legs and body, so much bigger than a rabbit’s. I slowly bend down and lift Wilfred up to see it better and, in doing so, break the spell. The hare lopes off gently, unconcerned, its hind legs folding and unfolding like a lever behind it. The black stripe down its back and tail make it somehow more serious, less comic, than the bouncing white of a rabbit’s. I tell the children that in Suffolk some people believe hares are witches who have transformed themselves so that they can play tricks or perform evil deeds without anyone knowing. As the dusk falls, their imaginations start to see the hare’s true form in the long shadows of the oaks that line the field boundary. They are so sure that I start to see witches in the tree’s dark reflections too. It is only afterwards that I realize the luck of seeing one that day. A hare, some think, was Eostre’s consort.

The need to mark light and dark in some way stretches around the world. Nowruz, the Persian New Year, has been celebrated on the spring equinox for over 3,000 years. The Mayans even built temples to align with the sun on the equinox so that, at sunset, shadows formed the images of a snake descending the steps to symbolise the feathered serpent god, Kukulkan. And Glastonbury this year was a place of pilgrimage for those who wanted or needed to find a way to mark this old festival.

I have been thinking a lot about this balance of light and dark. When we are present fully in one, it can be hard to remember sometimes what its counterpoint feels like, or that it even exists.

Maybe this is why the spring equinox is something people still cleave to, so that even if they are unaware of the precise date there will be a point when they stop in the street or path or field and look up and think ‘the world has shifted’. The buds are visible; the birds are louder; the light stronger on their face. They are, briefly, in a liminal space, able to touch both past and future.

Last weekend I went to my friend Claire Whittle’s new farm in Llangollen, Wales. She came to it in an extraordinary way which you can read about here which is proof (like we needed it) that Great Things do not arrive in your life without you asking and working for it, but that if you are brave enough to put yourself out into the world, magic can happen.

Claire wanted to plant an orchard of heritage apples and pairs she got from ‘Tom The Apple Man’, whom she met at the Agroforestry Show. They were being planted in a small, triangular hill-top field in front of the farmhouse. We said we’d come and help.

Somehow she conjured perfect weather. I stood on a hilltop under sun listening to the haunting call of a pair of curlews and tried to put a spade through Welsh slate bedrock to plant my apple tree (Claire had saved me Cummy Norman because….well…..you don’t need an explanation for that one do you).

We did all we could to make sure the saplings grew. I swirled the roots in an inoculation potion from The Land Gardeners. We staked the trees against the gales that blew that evening. Piled manure on top. But, ultimately, planting anything is an act of hope. You plant a seed. You tend to it. You protect and feed it. You do so knowing that if you do not, it cannot grow.

It is like writing. It is like love.

After the orchard was planted we made a dead hedge a metre away from a new one Claire had recently laid and gapped up with new saplings. Unlike the dead hedge I had made before in Suffolk, this was mostly built out of huge cuts of willow and giant hawthorn brash Claire had cut down.

Ollie cut points into hazel stakes with an axe. Claire hammered them in either side to hold the hedge in place.

Our arms were shredded. A thorn pierced through my glove with such determination blood sprang everywhere. We pulled and lifted and teased branches into one another like a savage game of Tetris.

The dead hedge was going to be a habitat for birds, snakes, insects and other creatures. But, as well as this, it would break down into the soil and in doing so - Claire hoped - provide nutrients to the new hedge now beginning to grow next to it.

It was impossible on that hillside under the sun, with scratched and bleeding arms and hands, not to keep seeing something more in what we were doing.

I thought of Merlin’s book and the work he and Lizzie do at Cabilla to try and raise the profile of these precious habitats, introducing 3,000 people a year to the wonders of a rainforest without having to get on a plane to somewhere tropical. Without the pain that had visited them, they may not have found their way along this new path of resolve and light.

I thought how our dead hedge will enable the new one to grow. I thought how what has passed is not extinguished, even if we are no longer able to see, touch or experience it. It has led us to where we are. It has formed us, and where we go next.

I have never had a Five-Year-Plan. I have tried, as far as I am able, to trust my instincts, keep myself open, and hope that wherever I am being pulled will make sense once I get there. Sometimes I look back and realise how the pieces of my life have brought me to where I am: each one built upon the other without me being aware of it.

I hope you too think it’s helpful, perhaps, to sometimes remember this. That change may happen whether we want it to or not, but that what comes now exists because of what has come before.

Light and dark, moving in cycles, each unable to exist without the other.