I recently went to Margate on a mini-break with my eight year old son. The Turner Contemporary art gallery sits like a huge marooned ship towards the end of the bay and is mostly populated by self-conscious hipster new parents in their forties. The gallery knows this, which is why it has opened a sizeable play area within the gallery, walled and floored in blackboard so that small creative geniuses can let themselves flow.

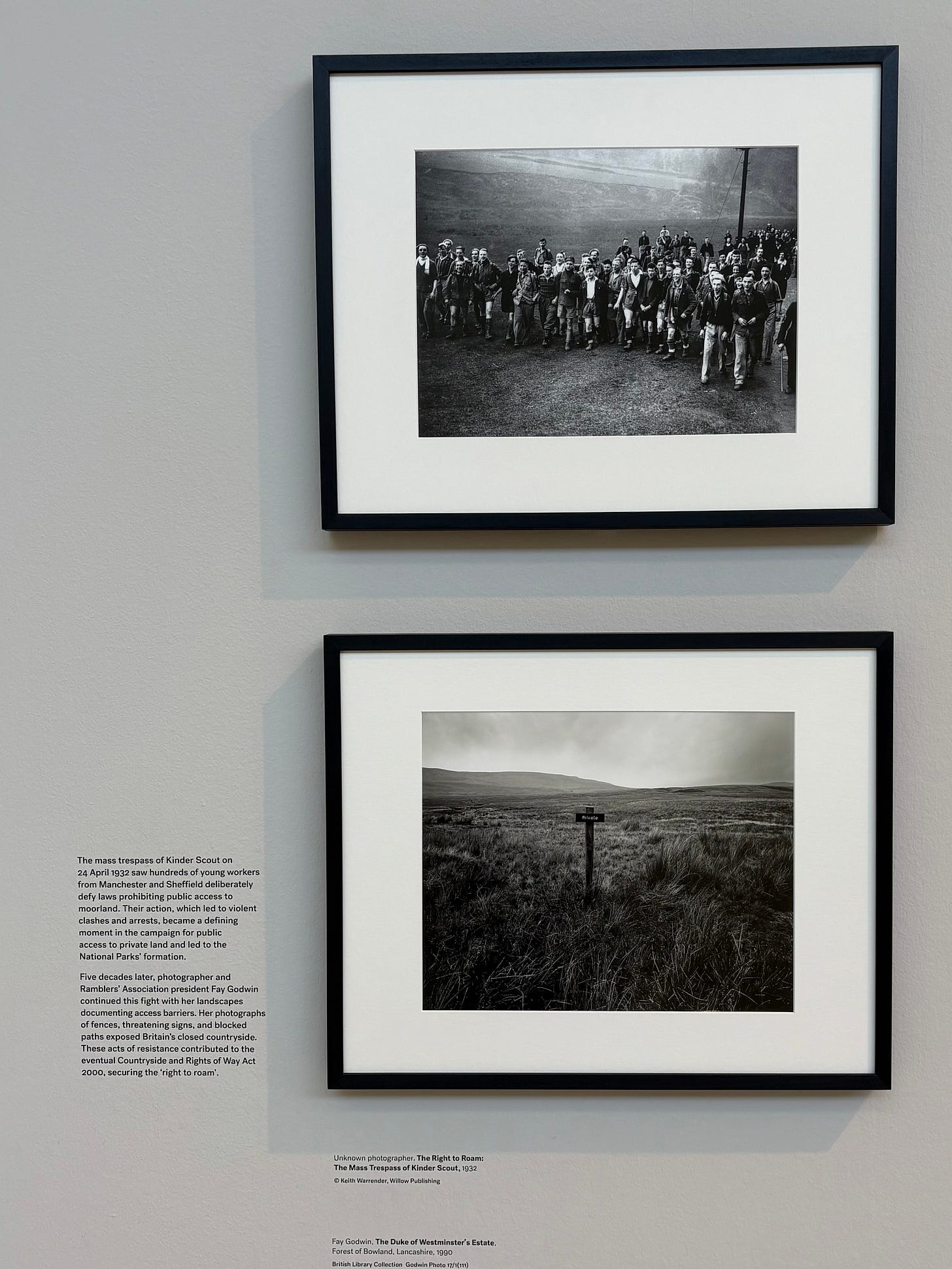

My son and I flowed in chalk for a bit but then I managed to persuade (bribe) him into the body of a gallery to see what was on. It turned out to be a subject I have been thinking about deeply for the best part of two years: protest. Around the walls hung many photographs in black and white of protests and civil disobedience going back a hundred years or more which had, or had tried to, change the law and so change history.

One was of a day exactly 93 years ago that month, which I had recently read about. On 24th April 1932, young workers from Manchester and Sheffield protested laws which prevented them walking on a moorland called Kinder Scout in what was later hailed the first ever mass trespass. When I had read about the men I wondered what they looked like. Now I knew (smiling*, tweed shorted, clean shaven, not a placard or drum between them**.) They seemed impossibly young.

*don’t get me wrong they got into various punch ups later in the march

**and a good number were arrested, so…

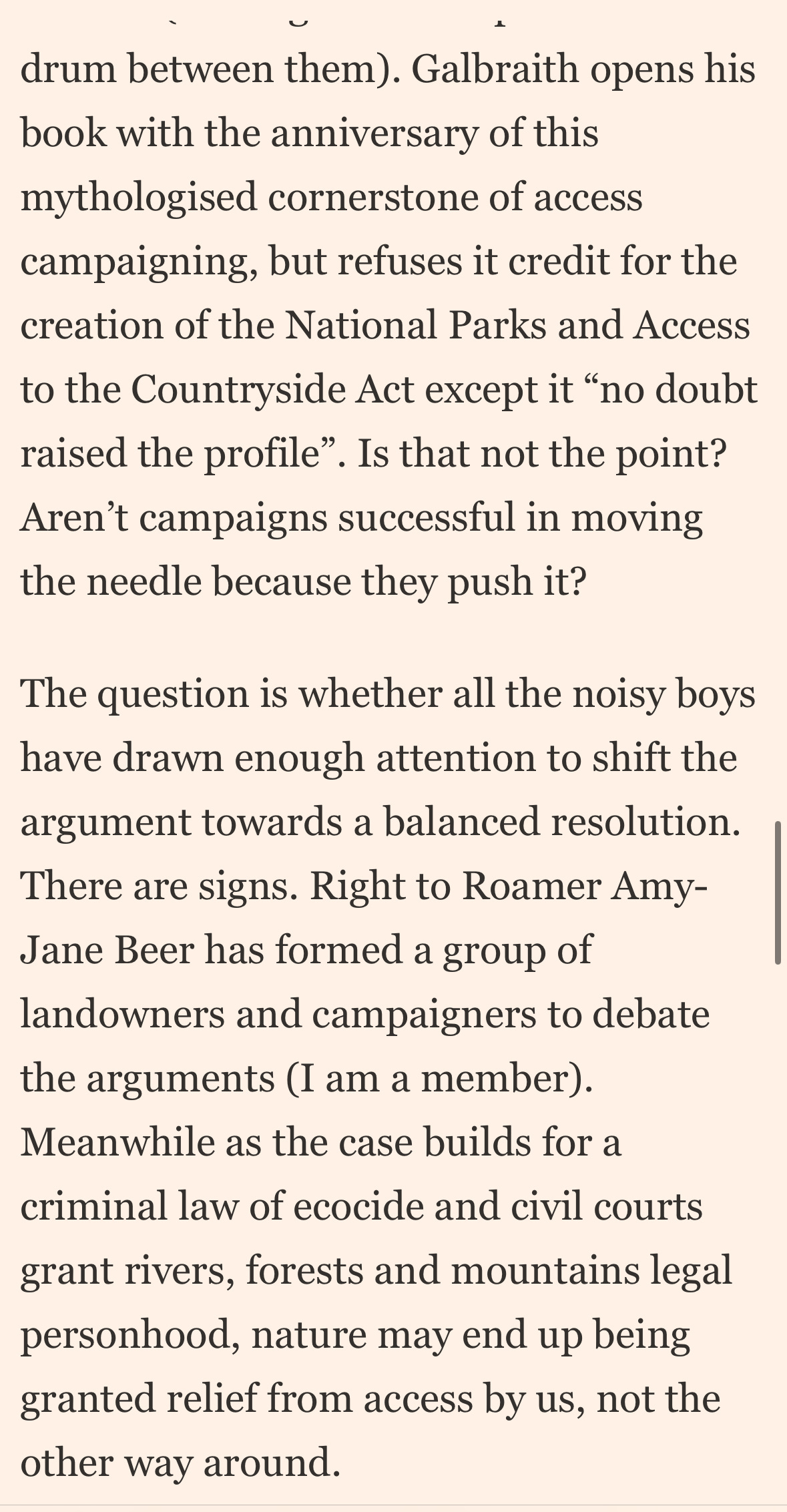

I thought of that picture again whilst writing a review for The Financial Times on a new bomb of a book by journalist, Patrick Galbraith. It is about the Right to Roam Campaign which has been arguing for the Scottish right of responsible access to be extended across the UK. It gives voice to the other side of the story in the form of often unheard voices such as poachers, gamekeepers and Landed Gentry.

The book has upset a lot of Right to Roamers, who have made allegations of being misquoted and say others in the book did not realise they were being interviewed on the record. This too is an allegation I have heard (directly) from some who appeared in books written by Right to Roam leaders. The back and forth bickering has made me a feel little weary, because whilst for those involved it’s galling and bitter and keeps them awake at night turning in the frothy injustice of it all, I suspect few others who read the books will worry about whether he said this, or that, or something a little bit different.

At its heart both this book and this debate is about a much more interesting problem (to me). Which is: what are rights, and who - or what - gets to have them. Which is kind of why I ended my review the way I did.

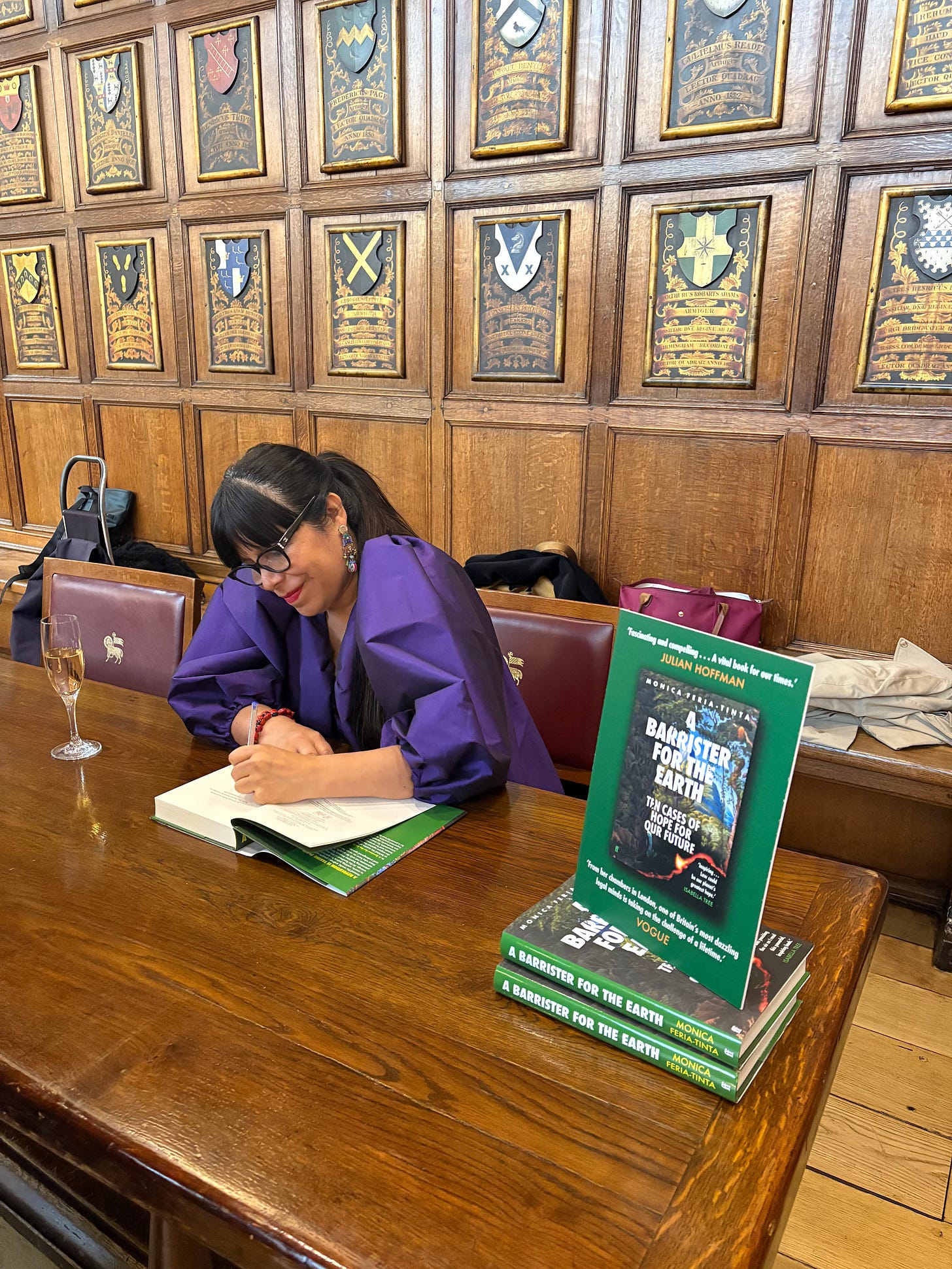

When I was away writing over the Easter holidays, I read a debut book recently published, called Barrister For The Earth, written by the British-Peruvian barrister Monica Feria-Tinta. It is about ten cases she has fought mostly on behalf of indigenous people around the world. But really, the book is also about ideas of rights and responsibilities: who has them, and how, and when. The idea of ‘rights’ has shifted and flowed through history and law, even if their legal definition has almost always lacked their reciprocal counterbalance - responsibility.

In 1913 a case called Bebb v The Law Society found that Gwyneth Bebb could not become a solicitor. Because she was a woman. And according to the Solicitors Act 1843, a woman was not a person in law.

It’s not so long ago really (I mean, I also learned that women were not allowed to open a bank account in their own name in the UK until 1975, just five years before I was born which is really not that long ago, so….). But the point Feria-Tinta makes is one I have been turning over. Once people thought it mad that the law would consider a woman a legal person. Now there have been cases where software (SOFTWARE?!) has been considered a legal person. If softwear, why not a tree? If a woman, why not a river?

There are already countries where rivers and mountains have been given legal rights. But if the natural world is given rights, how do we hold these in balance with our own?

I don’t yet know, but I can feel a shift in balance between our rights and those of the natural world coming in the way a good idea does. When everywhere you look the universe seems to be sending you a message or image or song or something that says: pay attention, something’s about to happen and you’ll want to see it when it does.

What I saw on the walls of a Margate gallery showed me too that often there must be a lot of noise before a tipping point of change is reached. People roar righteous indignation, bang drums, chain themselves to objects or one another. There is plenty of in-fighting, especially amongst those who feel their cause is pure. But following the heat there usually comes, in the end, light. Hard won, most often by those who bite their tongue and cross the floor and discovered their enemy not to be monsters after all. Just people.

Other stuff:

AFFLO, the access friendly farmers and landowners group I am a member of, you can read this piece about a panel I spoke on during the Oxford Real Farming Conference this January.

There’s an interesting FT piece by Phillippe Sands on rights for nature he wrote whilst reviewing Robert McFarlane’s new book

Here’s a panel I chaired on EcoCide which looked at how the law might protect nature with a bonus offshoot discussion about both how nature is defined in the dictionary (as separate from humans) and (possibly quite randomly) Luther

I love your always balanced approach Sarah. And so often the answer to things should be, I don't know, and I think, thats where solutions should come from - questioning and talking, not polarised views.

So much of this resonated, especially the challenge around who gets to decide what land is for. If we’re serious about a more just and nature-rich future, we need to talk not just about ecology, but about power: who holds it, who’s excluded, and how we open the gate for more voices.