Sometimes I sit on the tube and create lives for the people around me. We sit or stand close enough to touch, to smell each other, to notice stains or zips left accidentally undone. There is an intimacy in seeing the part on the back of someone’s head their hairbrush didn’t reach.

Still, we all collude in a fantasy of pretending this isn’t happening. We create a illusion of separation so we can cope with being this physically close to a complete stranger. Most people look down at their phones, which helps with this. Sometimes I do too. But other times I stare at people and create whole worlds for them in my head.

When I or they get off the tube, I will probably never see them again. They will be lost amongst the 9 million other people and 20 million tourists who co-exist with me in the city in which I live. I do not and will never know them. Maybe that’s why creating their life for them is fun. The fantasy can never be shattered.

Some life events and two recent conversations have made me think deeply about knowing people. Not strangers on the tube, but those in our life both in person and online. They have made me think about truth and about perception. So I’m doing what I sometimes do and writing it down here to help make it clearer for myself, if no one else.

I had a long conversation with my dear friend Clover Stroud about Hannah Neeleman of the account Ballerina Farm which is followed by roughly the same number of people that live in London. She wrote about how she feels about it here.

We talked about whether the fetishisation of domestic life as a ‘trad wife’ was dangerous and harmful to hard-won, short-lived and currently-threatened women’s rights (her view)*. Or whether making out that the raising of eight children and the running of a farm and business was effortless was just fantastical, lifestyle soap; no more or less than reading a glossy magazine where you (should) know that the airbrushed subjects are probably being photographed in a show home, and if you don’t realise this then that’s on you (my view)**.

We all make up stories about people we see or know all the time, of course. Stories are how we understand the world, which is why novelist Elif Shafek is right to say how powerful stories can be. Now our lives are lived partly online or in a public forum of some sort, there are more stories and the truth can feel hard to hold on to. But our online world is just a global extension of the kind of village life many of us would once have been part of. Anyone who has ever lived somewhere small will recognise both sides of the coin the close intimacy of that kind of life brings. On one there is the feeling you are being looked out for: small chats in passing, smiles and waves and greetings called out across the street, your family’s milestones celebrated by a community. This familiarity can feel like a solid floor beneath your feet. The other side of this is that gossip and conjecture are its life blood. This can make it feel less like a floor, and more like a box.

A friend once told me about her brother in law, who had hurt his shoulder and booked a masseuse to come to their house. Later that day, in the local pub, he was ordering a pint. As the barman pulled it he looked over and wryly asked ‘Enjoy your massage?’. The masseuse had left an hour ago.

The anonymity of a city like London can feel like a tonic to the magnifying glass of small-town life. I wrote a bit about this duality - what is lost and what is gained - in my book Rooted.

I start to wonder whether it is not just what we call our food that lets us separate our eating of it from the truth of what it is, although that helps. Cities, generally, help us to distance ourselves from all sorts of truths and responsibilities. Drop a can or cigarette butt or crisp packet in the city and someone else will soon come along and sweep it up for you. Here, in the countryside, it will stay until it is buried by leaves. Leave a gate open in the city and no one will be able to tell whether it was you or one of the other hundreds of people passing, and what does it matter anyway. Here it can mean cows running up the high street and sheep grazing on someone’s front garden. Pass a stranger in the city and you can look straight through them, for they are the hundredth stranger you’ve seen that day and you will probably never see them again. Pass a stranger in the countryside and you will be unlikely to cross paths with anything less than ‘Hello’.

I begin to wonder whether our solipsistic cities have promised us that we need not really be responsible for anything but our own wants and desires. Many of us have utter liberty to be who we want to be, which means that, for a lot of the time, we can behave how we want, dress how we want, party how we want, eat what we want, listen to what we want, read what we want, say what we want (although mostly to people who agree with us, unless it is behind a Twitter avatar). Maybe this is right. Maybe this is progress; maybe this is freedom.

But still, the consequences of our choices are often kept hidden away from us as though we are children. God is dead; so is society. We are told that the only person we need to be true to is our own authentic self, but when we look within ourselves for answers to life’s biggest ques- tions we are shy to say when we find emptiness instead of insight. In all this there is room only for life, and none for death. Death is kept away from us: hospitalized, ster- ilized and shrink-wrapped. Maybe that is one of the reasons we try so hard to ignore it, to escape it: the only event certain to befall us all. Maybe that is why it can be so shocking when we must finally confront it.

What is true of both is that we do not ever really know all sides of someone’s story.

Two formational life experiences have taught me that truth has as much to do with perception as it does with fact.

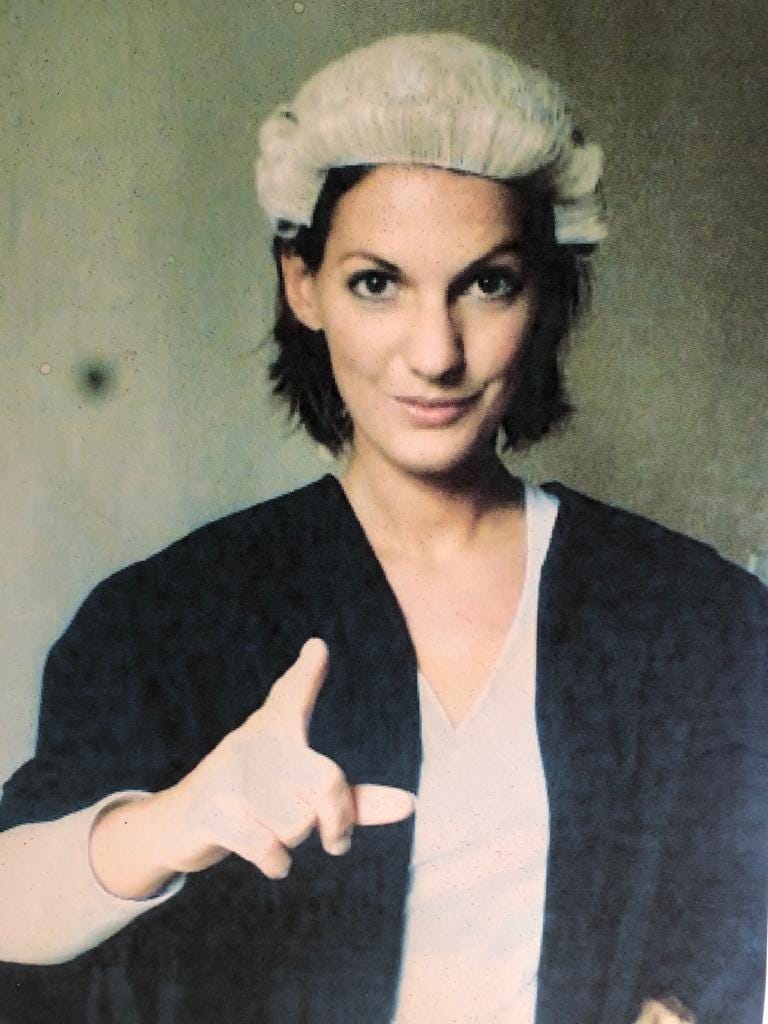

One was being a barrister for nearly a decade, where I spent my days listening to people give an account of what, more often than you might think, they believed to be the truth. When it was pointed out to them - or the jury - that their memory of what happened cannot be right - let me show you the CCTV; the other four witnesses say he was holding a glass not a bottle; here is a print off of the messages which shows they do not say what you claim - it could feel in the heat of the moment like pulling a rabbit from a hat. It was less magical for whomever was in the witnesses box. I would watch their confusion as what they firmly believed to be real fell away beneath them.

The other was my time as an outrider in politics. It made me realise there was always another, often more nuanced story, than the one in the headline. But it also made me realise that narrative is king. Whomever gets to tell the story, gets to define the truth.

The other conversation this week was with the mother of my son’s friend. I do not know her well, but what she said made me think a lot. “Wow Sarah I had no idea” she said. “You always just seem so in control and….together”.

Friends: right now I do not feel in control, nor together. But this is what she saw. This is what she believed. This is what she thought was true.

None of us really tell the whole truth about what is happening in the background of our lives: the unmentioned 5am graft, the moments of shouting or crying or hurling of butter dishes***, or the unseen hands**** (and funds) that support us. These are hidden by us for many complicated reasons: shame, pride, disillusion or need.

I don’t know whether we have a responsibility to share all this rather than creating an illusion, with occasional flashes of confessional honesty. Most do not. So I suppose it is good to remember this, instead. There will be another account. There will be many reasons for someone’s success or, for that matter, failure - some earned, some not. But what is certain is that silently woven through the lives of everyone we see, in both our digital and real world, are corresponding threads of privilege and pain.

So I guess all this means is that next time I create a story about someone - stranger or not (like this guy with a fantastic tash (not pictured) that I did exactly this about yesterday) - I will try to remember that.

*the ultimate howl-with-laughter-and-read-it-outloud-to-your-friends ‘day in the life’ piss-take is, of course, Tom Hollander’s. If you haven’t yet had the gift of reading it, here it is. You’re welcome.

**the book Doppleganger by Naomi Klein is brilliant on our duel real-life-online-life existances and especially good on how the world of wealthy wellness-wives and alt-right became blended - highly recommend

***something one of my most calm, sweet and elegant friends once confessed she had done, and I was so delighted by the fact that even she had moments where she was overwhelmed enough to lose control, which felt like permission to think that my own might not be madness after all, that I have never forgotten it

****I wrote in Rooted about the fantasy that nature writing has historically created: a genre dominated by white, middle class men who go ‘exploring’ with no mention or reference to the people in their lives which make these prolonged absences possible.

I am determined to learn about this new life I accidentally find myself in, and so I start to read nature books – bestselling ones, not academic ones – which then just tell me how much I do not know. The authors’ paragraphs are littered with names of flora and fauna, insects and birds, and I find myself skimming over sentences made up of words that make no pictures in my mind. This world of nature they describe seems a reverent and unknowable one. Sometimes it feels like it exists in a perspex box that the authors are studying, carefully turning it around in white-gloved hands for examination. I find myself looking for the nature I am living in, which bites and stings, burns, scratches, unbalances, whips and bends with wind. With the memory of birth so vivid in my mind, I know that nature is frightening, uncontrollable, animalistic, unsentimental. That it can hurt as often as it can heal.

I wonder often how the writers can go for such long walks without other people needing them. How are they free to stride into nature for days, weeks, years at a time so they might describe it to me? Maybe they have chosen a child-free life, the better to be wolfish. Or maybe there is a silent supporter left at home with weaning spoons and potty-training pants and a Calpol syringe lost down the crease of the sofa. Nietzsche wrote: ‘Only those thoughts which come from walking have any value.’ But then I don’t suppose he did it with a baby on his back and a toddler by his side, trying to separate his valuable thoughts from the babbled commentary of a newly discovered world.

The best piece of writing I have ever read on this is ‘A Lone Enraptured Male’ by the poet Kathleen Jamie, whose excoriatingly funny literary criticism of nature-writing hero, Robert McFarlane, is one of the most sharply brilliant things I have ever read and contained this blistering passage.

‘All of this is preliminary to the admission of a huge and unpleasant prejudice, and here it is: when a bright, healthy and highly educated young man jumps on the sleeper train and heads this way, with the declared intention of seeking ‘wild places’, my first reaction is to groan. It brings out in me a horrible mix of class, gender and ethnic tension. What’s that coming over the hill? A white, middle-class Englishman! A Lone Enraptured Male! From Cambridge! Here to boldly go, ‘discovering’, then quelling our harsh and lovely and sometimes difficult land with his civilised lyrical words. When he compounds this by declaring that ‘to reach a wild place was, for me, to step outside human history,’ I’m not just groaning but banging my head on the table.’

This is so wonderful—thank you. I loved reading this.

thank you for this and introduction to Kathleen Jamie's work.