Orchids at Kew

Kew is somewhere I once considered just a glorious giant garden I could get to on the London underground (even the station is pretty lovely).

It was filled with lights at Christmas, had a playground big enough to burn off small-boy energy in a few hours, a bridge to rattle sticks over and a walkway to chase children around and around high amongst the trees.

Friends: I was wrong. In fact, Kew Gardens has an extraordinary history that dates back to 1759 when it was established as a modest royal garden by Princess Augusta, the mother of King George III. It evolved into a place of botanical research under Sir Joseph Banks, an influential naturalist who advised on global plant collection during the 18th century.

Today it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site that houses over 50,000 living plants. It has global reach, playing a critical role in conservation, research and education in countries on the front line of climate change all over the world.

When the nuclear bomb hits or our crops finally fail, it might be Kew Gardens who saves us. Because what so few people know (including, until a few years ago, me) is that it houses the Millennium Seed Bank at Wakehurst, Kew’s countryside estate in Sussex. This seed bank preserves the world’s plant biodiversity by storing seeds from species at risk of extinction: over 2.4 billion of them. It is the largest seed bank dedicated to wild plants and so ensures the survival of rare and endangered plant species. It is, in short, our insurance policy against climate change, deforestation, and environmental threats.

But apart from all this Kew is also really, really beautiful.

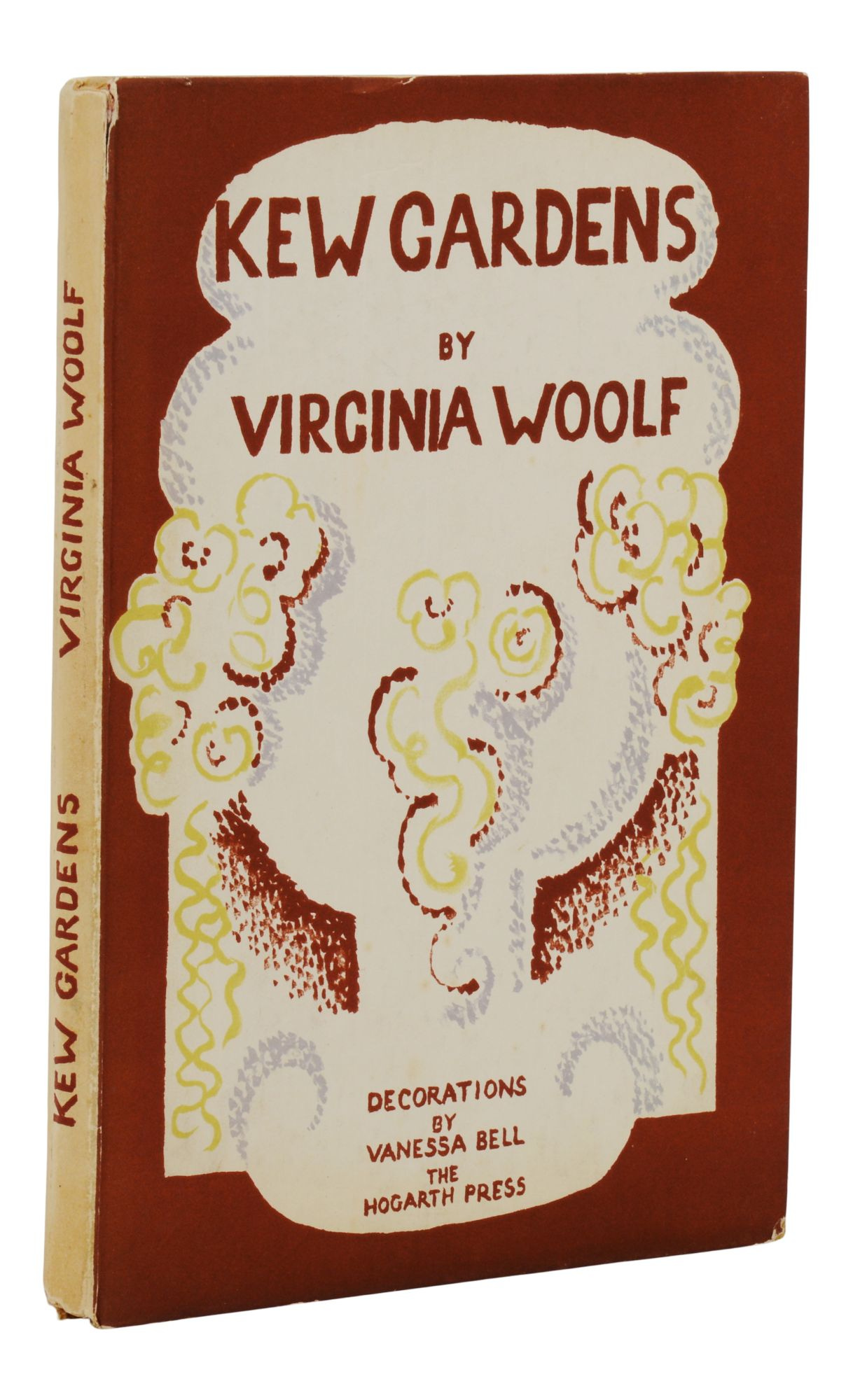

I realise I’m not the first to say this. Virginia Woolf - who has been on my mind recently after reading many of the love letters between her and her lover Vita Sackville-West (the loveliest being the one below) - wrote a short story in 1919 called Kew Gardens (clearly sometimes it’s best to be straightforward about titles) where she wove together the observations of different visitors, drawing out the interplay between nature and human contemplation.

Virginia got it. But what I had failed to understand was just how much more Kew was than place for strolling octogenarians or plant wonks. I now know Kew do things like yoga in the glasshouse, forest bathing, tai chi, pilates and so on. A friend rhapsodised to me about their sound baths, which are now running from 9th April to 8th October in the conservatory.

Then there are Kew Lates where the glass of the greenhouse vanishes into the night sky above it making it totally magical. I’m reliably informed they clock up numerous proposals under their flower arches. They’ve got some coming up in the summer.

They also have a podcast, one of which is about soil and has some excellent guests on it…

Anyway all this I now know because I have somehow ended up on the guest list to openings of new exhibitions. Each time I go I learn a little about the conservation work Kew Gardens do all over the world, and a lot about a place or plant, which is worth a trip on the District Line. But also, where else can you find a DJ and a waitress dressed like an acid-rave version of a Georgia O’Keeffee painting.

Or where else can my friend Harry Briggs perform Queen of the Night to a cactus of the same name, which only ever flowers at Night. Clearly someone took their cue on the name from Virginia.

But this time I learned about both orchids and Peru*.

Apart from the Peruvian ambassador telling us about all the work that happening to preserve the 27,000 species of orchid, 56% of which are at risk, my main takeaway for the night came from Kew’s Director , Richard Deverell.

The name orchid comes from the Latin word for testicle.

You’re welcome.

I ran into some mates in the sustainability world, like Amber Nutall and folk singer Sam Lee who based on this photo is clearly hilarious.

But my favourite person to talk to if I ever get near him (for he is, of course, the star of the show) is exhibition curator, Henck Roling who always dresses to match the exhibition. Again: I know. This is me, my friend Kate and Henck at the Madagascar exhibition.

Most of all, though, each time I leave I am reminded by the simple truth of how much we have to learn from nature about how to live.

One of the best examples of this I included in Rooted, which took place at Kew after fifteen million trees (yes that’s not a typo: I checked) came down in The Great Storm of 1987. Here’s what I wrote. It is about why this story changed how it felt to leave an old life and start a new one, in case anyone else needs to hear this now too:

I cannot work out if everything around me is changing or if it is just that I am noticing it. The only thing I am sure has changed is me. I find myself thinking of a programme I once saw about an ancient oak tree at Kew Gardens in west London. In 1987 a storm blew in from the south-west of England that felled fifteen million trees. In Kew Gardens, the 200-year-old Turner’s Oak was heaved up by the wind and then dropped back into the earth at an angle.

Before the storm the tree had been unwell and struggling to thrive for some time, although no one could work out why. They were sure that the ripping up of its roots in the storm would finally kill it off. They propped the old oak up with planks of wood so it was not a danger, then began to chainsaw the Gardens’ other 700 fallen trees into pieces. There was another reason they left the old oak until last. Tony Kirkham, head of the Arboretum, was fond of it. The idea of having to cut it up was so sad that he wanted to put it off as long as he could.

It took three years to clear all the other trees. But when they returned to the Turner’s Oak they found it growing, strong and healthy, no longer sick. They realized that when the storm lifted the oak from its roots it pulled the soil apart. Air rushed in. When the oak fell back to earth it pushed air down into the soil making it porous, allowing oxygen and water to reach the roots more easily. The soil around the tree had become compressed by the weight of thousands of visitors. This was why the tree was dying. After the storm the tree put on more than a third of its growth.

What happened to the Turner Oak changed the way that trees are looked after not just in Kew, but around the world. ‘Trees are like people,’ says Kirkham in the programme. ‘They’re moody. They stress. But they’re beautiful when they’re happy.’ Now I think how our old life felt like it too was ripped up from its roots. As it turns out, it just needed some air.

If you want to see the short film you can watch it here and I dare you not to well up when Tony Kirkham also wells up at what The Turner Oak means to him.

Now March brings with it hope and light and life, coming for me at exactly the time I needed it to. Maybe for you too.

So I will end this on something else I wrote in Rooted about the lessons we can learn from the natural world; lessons I would have done well to remember over the last few months.

As I walk back with the wood over my shoulder, I look at the fields either side of me, sloping up and away from the road. I think of a new farming word I have learned from the reading I have been doing: vernalized. The seeds of some plants, such as winter wheat, need to go through a period of intense cold to be able to flower, which, for wheat, means the growing of grains. Vernalization, which comes from the Latin vernus, ‘of the spring’, can happen only if the seed is exposed to the bitter cold of winter.

I think how winter is not a deadness. It is not an absence, either. I am learning that this time is a necessary part of the life cycle. It is in winter that the frost creeps its way around ploughed soil, freezing and swell- ing the water within the soil particles and cracking it into a fine tilth ready for sowing. It is winter that brings other seeds to life, the frost softening their hard seed coat so that the seedlings might germinate and grow, searching for sun and nutrients. But maybe it is not just plants that need to undergo a wintering before they are able to grow or flower. Maybe we must too. I am starting to wonder if this accidental time away from everything I had thought was important – this time I had not planned, sought or wanted – might not be an absence of life at all. That it is more necessary than I had known it would be. That, maybe, it is me who is being vernalized.

Sarah x

*I promise to let you know about the next exhibition in time for you to actually go and see it, which would be slightly more helpful of me I know

Kew is blossoming - so much more going on than when you could get in for a penny.